“To see how ambiguous our history has been, however, is not simply to retire into that more subtle mode of complacency, universal and ineffectual guilt. Rather, as Abraham Joshua Heschel insisted: ‘Not all are guilty but all are responsible.’ Responsible here means capable of responding: capable of facing the interruptions in our history; capable of discarding any scenarios of innocent triumph written, as always, by the victors; capable of not forgetting the subversive memories of individuals and whole peoples whose names we do not even know. If we attempt such responses, we are making a beginning — and only a beginning — in assuming historical responsibility” (David Tracy, Plurality & Ambiguity).

This weekend, early on the morning of Sunday, June 12, 2016, Omar Mateen opened fire with an automatic weapon inside a gay nightclub in Orlando, Florida, killing forty-nine people and wounding at least as many others.

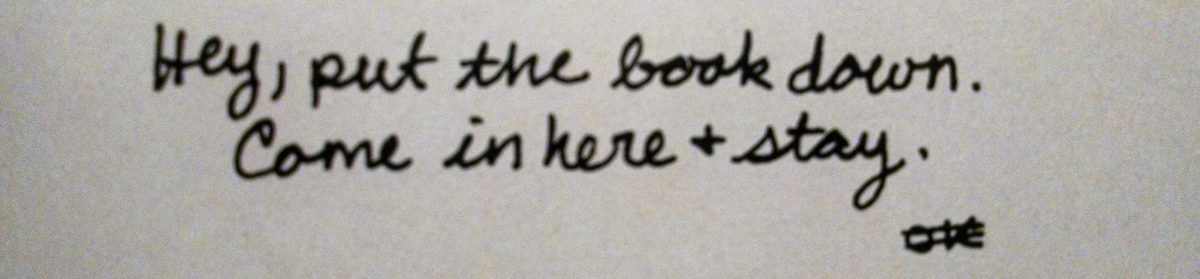

Meanwhile, I am privileged, normative, living hundreds of miles away in the American Midwest, which certainly leaves me with very little to say. I know that, and I know regarding that about which one has nothing to say, it is best for one to keep silent — especially where my friends have already done so much. The best I can do is immortalize this moment here, bear witness to it, show that I am thinking about it and will not stop thinking about it. Perhaps the most important thing I can do is make a monument here, a Beth-El, making sure that there is just one more waypoint through which someone can go on their way to remember the victims.

The only contexts I have for this are my books, my only interface with the outside world right now is my library. There’s something miserably dehumanizing about that. I learned of the attack just as I was finishing David Tracy’s Plurality & Ambiguity. Writing in 1987, in the heyday of cultural theory, Tracy, a Catholic theologian, argues for the power of conversation in navigating the intense plurality and ambiguity of our human condition — of our language, our history, and our hope. Confidently, Tracy describes the power of critical theory for the turn of the century:

Any theory that allows primacy to critical reflection is on the way to becoming critical theory. A critical theory in the full sense, however, is any theory that renders explicit how cognitive reflection can throw light on systemic distortions, whether individual or social, and through that illumination allow some emancipatory action.

Tracy goes on to describe his optimism in the possibility of such emancipatory action through critical theory: “The uniqueness of modern critical theories…is that our situation is now acknowledged to be far more historically conditioned, pluralistic, and ambiguous than theories like Aristotle’s could acknowledge.” Tracy cites such subversive and re-visionary voices as Michel Foucault, Julia Kristeva, and Edward Said as exemplars of this kind of thinking. Our power is in our awareness, says Tracy, and through the humility of our moment, we can pursue “genuinely new strategies of attention, resistance, and hope.”

Twenty-nine years later, the victims of Omar Mateen were not recipients of emancipatory action. The LGBTQ+ community as a whole, brutally reminded of their terrifying lack of safety in this world, is not experiencing emancipatory action. The Muslim community whose beliefs and ideals are being blamed for Mateen’s hatred and violence are not recipients of emancipatory action. Praying Christian communities, whose motives are questioned and even decried due to the Moral Majority’s long history of homophobia and oppression, are not experiencing emancipatory action. Despite all our awareness of history, plurality, and ambiguity, emancipatory action is a far-flung wish that comes fifty lives and more too late.

I guess I’m trying to say that, on a certain level, Tracy was wrong. Insofar as Tracy seemed to see a theological light at the end of the tunnel via the road of Critical Theory, I think Tracy may have been wrong. “The golden age of cultural theory is long past,” writes Terry Eagleton in 2003, and this sentence alone, it seems, is enough to blithely dismiss a number of Tracy’s hopes, as “plurality” is devolving into the viciously-policed boundary-lines of warring ideologies which have less and less patience for “ambiguity.”

“Indeed, there are times when it does not seem to matter all that much who the Other is,” continues Eagleton. “It is just any group who will show you up in your dismal normativity.” If I as an academic may be forgiven for saying this, Orlando, and all its echoes, represents just such a situation in which it ought not matter all that much who the Other is. As I write, processes of Othering are happening all over the place as people look for someone to blame: “There is just Them and Us, margins and majorities.” But there are also those who are choosing to stop Othering just long enough to help pick up the pieces of people’s lives, without caring whether or not these hands are gay, straight, trans, cis-het, Muslim, Christian or atheist, only caring that there are hands at all, hands to shore fragments against ruins.

I’ll be reading Tracy’s The Analogical Imagination next, the theology which under-girds the view he presents in Plurality and Ambiguity. Following him will be more of Eagleton, with After Theory (2003) and his recent Culture and the Death of God (2014). I want to know where Tracy failed, or where history and society failed him, and what explanation there might be for a society that just wants to fight about what’s happening to it rather than reason together. I want to know why just a few, venomous voices are allowed to dominate the “conversation” which Tracy once imagined so hopefully, cheapening the silence the rest of us keep not because we’re passive or afraid, overwhelmed by what Tracy calls the complacency of “universal and ineffectual guilt,” but because we’re just trying to take a few moments to focus on holding one another.

And, I want to know what to do next.

Praying for Orlando with a similar sense of helplessness and wondering what to do next.

LikeLike